From Essays And Work

Circa, 2016.

On Time

I

You think you are the string through the beads, that eventually someone will tie you off, add the clasp and hang you—a complete and pretty string of beads. But instead, one day the hand will let go and the beads fall off or scissors will trim you and in any case, the beads will all go perhaps not even rattling away.

II

A woman discovers time. That is another way this could begin. Time for herself? To herself? No. Time. The woof and weft of existence. She sees where its threads go and pulls them where they come up. When she tugs, it hurts.

Augustine is our great male hero. He philanders until sex is dull, then he gives it up and righteously abhors it and all who enjoy it. He works when he’s not bothered with desire. After he’s fathered and left. He messed up, he can recoup, confess, get his body back.

She can’t have her body back from desire. Desire has erupted from the inside and she was stitched up.

III

“ ‘I don’t want to die! I don’t want to die!’ screamed Wilbur…”

This—not the scene when Charlotte writes her web and saves the pig—is the climax of E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web: this scene when Wilbur discovers he’s about to be killed.

The hero, if this is the climax, is the reader not Wilbur. The reader hears Wilbur’s cry and realizes the suffering of animals, of the animal’s self, a string about to be cut. Wilbur has realized he is being used, his existence is a tool, a standing reserve, a ready-to-hand store of fat and protein for the humans who pat him and feed him. From this, we draw back as one, das Man, does, as Heidegger did. We withdraw from Wilbur’s suffering as they draw back—what a horror that a young pig might realize his fate, what a horror factory farming, what a horror consumption—and also, we realize that we are Wilbur.

I don’t want to die. I am eating only to be fattened up for death.

Why not be like Simone Weil and starve oneself to death? In starving, writes Weil, one feels afflicted, one senses the affliction of embodiment, the injustice of it.

From that moment of revelation in the text, the farmers and their methods must be the only study of Wilbur’s life. As the reader, I too, take up this study. Time is the only subject of my life’s study. How can I cheat it? And if not that, then how can I accept it? The more I think about it, the more I merely want to cheat what seems an unfair rule.

Charlotte’s Web is a story of injustice. An injustice for Wilbur, for all animals, for a life. Every story is a record of injustice. With the last page of the book, the characters in every novel end. And so, like every book, we end. You turn your last page, and that’s it. It is in its finitude that a book best represents life.

How we die seems to be a matter of chance, luck, touché, or luck tinged with irony.

But death, the fact that we die is a matter of justice. Most of us die without dignity, in pain, aged but still too young, without control of our bowels. How unfair, that we must all die like Wilbur. What kind of nature should cause us to be finite? How should we live, given this fundamental injustice?

Justice, dikaiosýnē, meant for the Greek merely “minding your business.” In the Republic, Socrates tries to find justice. On the way to that answer, Socrates asks his friends, Is not the business of the soul living? The friends answer yes. Justice then, would be living well, minding your own business of living. They determine that the opposite of living is dying. Thus, dying is an injustice.

An injustice occurs when, no matter how well you organize the regime of your city-soul, you die. Death is everywhere and unjust. Unjust that it happens to Wilbur, the kindest and most enlightened of pigs.

But if, there were to be justice, where would it be? Socrates asks. He asks his friend Glaucon, the "bright-eyed”—the bright-eyed young boy, the boy less than thirty years old, not old enough to notice mortality—to imagine an ideal city, an ideal soul, one without injustice. What would that city be like? asks Socrates. Where in that city would justice be? It would be, says Glaucon, “in the dealings of citizens with one another” in the city. The citizens might not deal well with one another if there is inequality. So, the best way to avoid injustice was to make sure everyone had an equal amount—to make sure no one had too much so that no one would try to take it from someone else. (In the soul, which is analogous to the city, the “dealings” are between desires and reason.) So, if we gave every citizen the right job—to bake, to fight, to birth—and just enough to feed them, says Socrates, then that would be the ideal city, the just city, the best human? Well, says Glaucon, it wouldn’t really be the best human city—those beings, fed just enough to live, would be pigs. People like a little extra. They like comforts, relishes with their meals. “But what would you have, Glaucon?” Socrates replied. “Why,” said Glaucon, “you should give them the ordinary conveniences of life.” Of course, with more than enough to live, people become comfortable, fat, fattened up for injustice, for death.

To be human, is to be as Wilbur found himself—reflective, fattened up and aware.

We ought to think about it: Whenever a horse stumbles, a tile falls or a pin pricks however slightly, let us at once chew over this thought: “Supposing that was death itself?’’ says Montaigne.

If we find no deity to appeal to, then we find that nothing justifies the difference between what is and ought to be. Is ≠ ought. We feel, if we have lived, that we ought to live forever. Nothing justifies the great gap between our belief that we ought to live forever and the reality that we do not.

Time is the subject because of the death of the subject. To subject is to be sub-jectum, to be thrown beneath, killed off, tossed aside.

Circa, 2016.

On Thinking

“Thinking does not bring knowledge as do the sciences. Thinking does not produce usable practical wisdom. Thinking does not solve the riddles of the universe. Thinking does not endow us directly with the power to act.”

That is the later work of Martin Heidegger quoted by Hannah Arendt in her later work. Arendt sampling Heidegger. In their later work, their later lives, they write the difference between thinking and knowing that. Thinking and doing at once became closer and father away. Thinking was itself the best sort of self-contained Action. Thinking “does” nothing—achieves nothing economic, physical, catalogable—and yet in its very non-doing accomplishes much.

And what is thinking?

Thinking is a way of doing nothing, making nothing, not even work. So thinking shows and does not show in the work.

“There is action in inaction and inaction in action,” counsels Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita. The same counsel is given by Arendt, sampling Cato:

“Never is he more active than when he does nothing, never is he less alone than when he is by himself.” Numqum se plus agree quam nihil cum ageret, numquam minus solum esse quam cum solus esset.

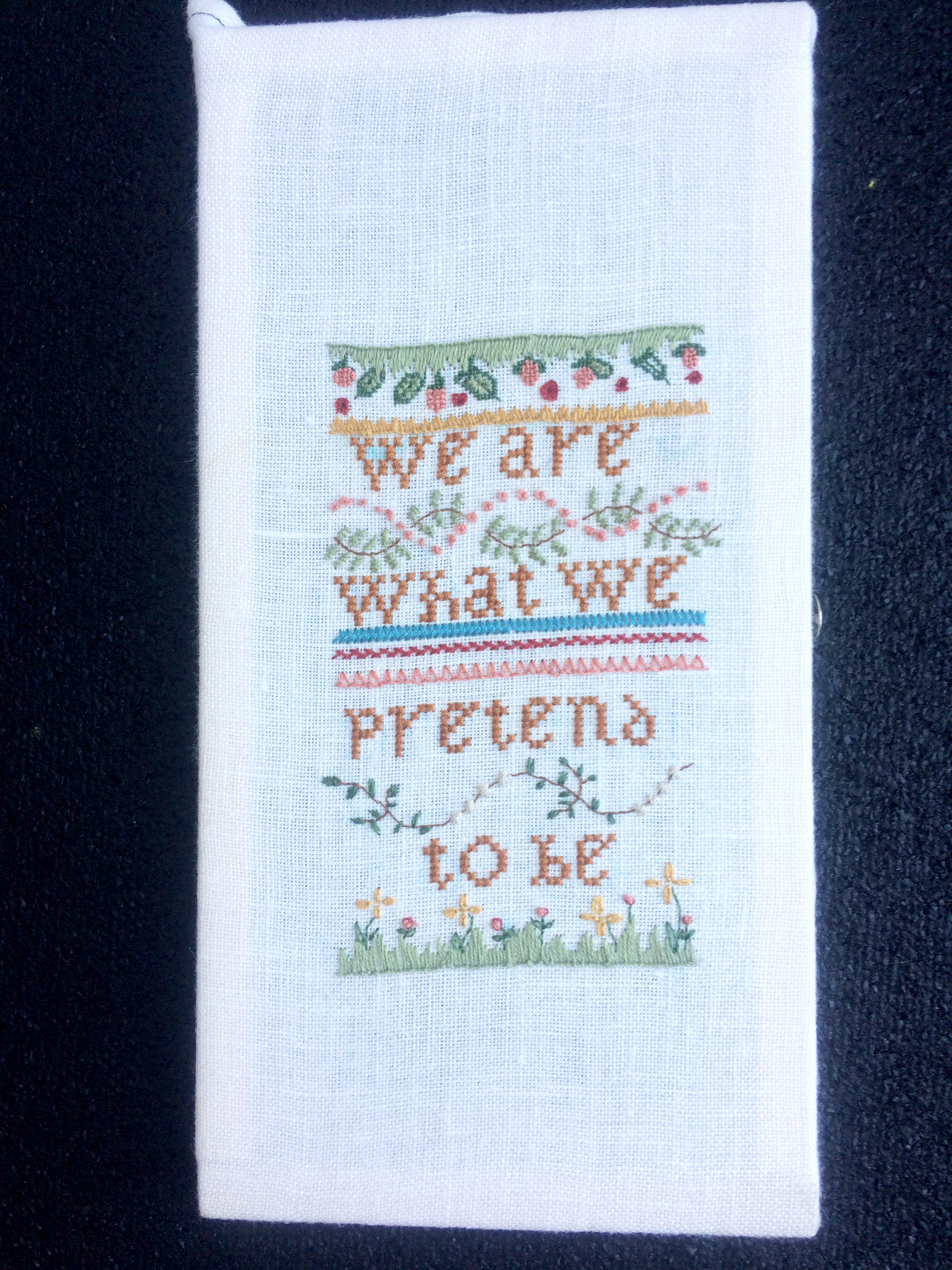

Sewing, for example, is a way of doing nothing and thinking. To approach thinking as doing. To withdraw to the company of thoughts. And to stay with a thought, a single thought. Patience is, or was, a virtue. Never one that I had. So this is difficult. It is work to think like this.

To stay with a thought. To really think it. To let it be. To think intensively, not to think the extensive, many worded thinking-reading of scholarship “accomplished” on-line, in catalogs. To let myself be as only thinking. And a little stitching to draw together the mind, the body, and some threads in the world.

Thinking tugs on each intentional thread, the fabric of ex-sistence composed of les fills intentionales and binds them together in pattern. That is thinking.

“Et comme la genèse du corps objectif n’est qu’un moment dans la constitution de l’objet, le corps, en se retirant du monde objectif, entraînera les fils intentionnels qui le relient à son entourage et finalement nous révélera le sujet percevant comme le monde perçu.” Merleau-Ponty

Circa, 2014.

On Respect

“Duty and Desolation” is the title of a great essay by Rae Langton. This little essay deserves to be read perhaps as much as the Kantian texts that prompt it.

It is an essay for which I have deep respect, and it is that respect that I wish to discuss. Not Kantian respect, though Kant’s work is one subject of respect. I respect Kant’s work even if I see him as flawed, incorrect, limited. His words bear repeating. The threads of his thought run through the fabric of contemporary thought, are stitched in to me, into your concepts of mind, body, person. So we should read Kant. But we should also read Langton.

Here I sample Langton’s essay which in turn samples from Kant and from a woman named Maria. Langton respects them both, as do I.

Maria is Maria von Herbert, who wrote to Kant—explains Langton—of a moral dilemma he addressed and an existential one he did not. Maria’s letters show that she understood the rigor of Kantian ethics, which can be summed by the demand not to make an exception of one’s self. You may not lie, you may not use others as tools, you may not even prevent the murder of your mother if it entails you lying, because that would permit you to be an exception to the universal rule “do not lie.” You know you shouldn’t do this if you use your Reason. (If you don’t know this, then you are not really using Reason, says Kant.) Desire and love do not a moral decision make for Kant; only Reason ought to guide action.

But Maria. She did not let Reason guide action in one situation, and then she suffered. So, she writes Kant for advice. She lived honestly but for one lie to a friend, a would-be lover, as is revealed later—but not at first to Kant. She revealed the lie—to “a friend”—and he dumped her. Bereft, desolate, she wants to die, but Kant’s morality forbids it. What should she do? she asks Kant, appealing to him, she says, “as a believer to a God.”

Kant did her the service of replying at length and seems to consider the details of the situation. But details don’t matter very much to Kantian ethics. The point is to follow the rules, rather than to change them to fit the details of a particular situation. That is ethics: following the universalizable rules. Are these ethics for lovers, mothers? For women? For people? No. Kant doesn’t love you. And even if he did he wouldn’t think it was relevant to choice. He speaks of respect, rationality, and advocates detachment more avowedly than any conservative Buddhist or yogi. If all humans by nature desire to know as all trees desire light, then to be a tree is to desire light and to be human to desire knowing. To be alive, to desire. To be a Kantian is to die, to not let desire guide life.

So, Kant told Ms. Herbert that she should live, albeit unhappily, with the consequences and that anyway “the enjoyment we get from other people is vastly overrated.”

After pointing out how heartless is Kant’s reply, Langton’s essay explains the ethical problem with treating other people merely as means, as we do, for example, when deceiving them, as Maria did.

Kant inquired after Maria and responded to a second letter, but when he discovered, through a mutual acquaintance, that Maria’s deception was due to romantic love, he dismissed her entirely as an “ecstatic woman” and even mailed her letters off to a female friend as a “cautionary tale.” In this dismissal, Langton shows, Kant made an object of Maria. She was a tool, her tale one to use to guide other fallible women. Kant does not live by his own philosophy even after admitting that philosophers might be held to task for such.

Maria, of course, killed herself.

Of course? You might say. For Maria, this was the only course, to end her course, to end her movement forward, her life. She had no desires left. That was, for Kant, okay. Desires don’t tell the Kantian what to do. Kant acknowledges that there are desires, inclinations. We are human. It is the case that desires prompt us, could motivate us to act. But the Kantian does not let desire motivate her. Only respect for the moral law motivates her. Reason, determining objectively what ought to happen, decides action. Maria was a true Kantian. She knew Is ≠ Ought. Rationally, she knew this. But with reason as her only motive she could not live a human life. Lost, desolate, abandoned by desire, with the company only of Reason, she wanted to die. Whether suicide is permissible by Kant depends on which Kantian text you pick up, but there is no question that Maria took reason and consistency all too seriously. More seriously perhaps than Kant, for she saw that existence put her into contradiction with reason.

Kant did not see this. He did not see that living was incompatible with being motivated by Reason. He let his inclination to belittle a woman, to prefer that his philosophy was not deadly, trump the reasoned statement that Is ≠ Ought, inclination need not guide life, desire has no place in ethics. Even desire for life.

Imagine living to be incompatible with reason. Imagine respecting that.

So Maria dies and Kant fails to be Kantian. Why does Langton tell us this? I think it is because she nonetheless respects Kant. Respects, as in, approaches with an attitude of treating as a human with rights.

Near the end of the essay, Langton writes, “Enough. This is not a cautionary tale of the inability of philosophers to live by their philosophy.” Why not? Why could she not write that? Why could she not simply dump Kant as Maria’s lover dropped her. He failed to live to her ethical standards and contradicted himself. Yet Langton canonizes his text. She respects him. She comments on his writing and in doing so, recommits it to classrooms and conferences and conversations. And I comment on her. She reconfirms Kant in the canon, but she canonizes Maria too, in a double sense. She calls her “a Kantian saint.” One so close to the God that she leaves us behind. We cannot all act like Maria because we are not saints. And indeed the point of Langton’s essays is that we ought not act like Maria or as Kant instructs. Kant would have us act as if we live in an ideal world. But this is ethical error. We should not act as if we live in the Kingdom of Ends—because we do not: we live in history, this history and situation of injustice, and failing to notice that is an ethical failure of a different order.

Langton does not love Kant with the abandon of Maria. She works hard at his texts, all of them, picking through his work to help him be consistent, to make more meaning than he made, to make him clear to her readers today. Langton had to know Kantian ethics to get a job. But the essay also truly respects his work. She assays it. She weighs it. It’s not just one theory among many that she read before she saw the light and wrote on Rawls and then on her own. Her essay displays a respectful interest in understanding this author whose concepts thread through so many others and her own.

Thus I do not merely walk away from the Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals judging it inadequate for life. I do not walk away from Reason. I walk regretfully away. Reason is a big, beautiful black book with an architectural structure to rival Palladian villa. The architecture leads us up away from the everyday to a viewpoint over existence. A beautiful building, a sturdy construction, but misplaced, a Venice in the sea. A palace when we are starving.

If we have full bellies, we can appreciate its structure even if it is now more like art than thinking.

Circa, 2014.

I

What is choice?

Let us think together about this. We would begin by asking, What is experience like? Let us think together in images—St. Thomas found this permissible—in an analogy, or better a metaphor, wherein the physical gains a dimension, a fourth. In thought, the visible soaks the invisible, invisible suffuses the visible.

Which image?

Let us imagine a skier—among a fleet of skiers—heading down a hill. The skier—skillful, telemarking—navigates obstacles, follows others ahead of her through particular routes, and executes turns. She flies and flashes. She learned to ski better by watching others, by mirroring their motions, by trying to catch up. Particularly hidden are her first actions: she cannot remember the release to the hill, she cannot remember the first slippery steps. Our skier has always been skiing; it is as if she woke up one day and found herself already skiing. Safely gliding on her trajectory, with some moments of leisure, she might reflect on her movement. She might ask herself how much of her movement she is responsible for. But she is a downhill skier: motion always accompanies her meditation. No sooner does she reflect than she makes another choice.

What is the source of the momentum described in our analogy?

The force would be roughly the force of our initial push plus that of gravity (minus friction). This momentum includes the womb plus a sort of general “gravity” of the plurality into which we are born. We both carry ourselves and are carried along by this force.

You spoke of a fleet. Tell me about the other skiers. Can she see them?

She expects to see them even when she does not.

The excess of perception points toward expression; the center of subjectivity points toward intersubjectivity.

Where did the skier begin?

At the top of the hill. But in our image, our metaphor that we are thinking together, she has always already been skiing down.

So the skier didn’t choose to ski?

Our beginnings are lost to us. Like Proust, we find that we do not coincide with our beginnings—the new madeleine only points to the distance of the narrator from the first experience. At the same time, natal beginnings occultly influence each present action, each perception.

The fact that we participate in the birth of the world does not mean that we are the author or inventor of the world.

My existence, my “I,” unfolds in a situation. I unfold dynamically in time, carried forth by the momentum of my birth.

Fine. She didn’t choose to begin. How does the skier choose where to go?

A topographic map will not help the skier manage a difficult pass as she flies along. The information about my genome will not help me—in the moment—know the source of my anger, joy, or intention.

Like the artist in the famous video of Picasso “drawing” a bull with a light in mid-air but no canvas, the painter must feel the action from the inside.

The skier guides her movement from within, without a view from above, navigating within the parameters of her natal momentum. Prereflective, theoretical knowledge of nature’s contribution to action is unavailable in the moment of action: she can only sense her general practice of taking up situations. The lack of this privileged knowledge in prereflective existence—the lack of a true Kantian critical standpoint—does not absolve us from action or even from understanding the situation.

Well... Does the hill force her course or does she choose her route?

Here are two interpretations of what is happening with the skier.

If motives are strong—undeniable instincts, for example—then we are not free (as in determinism); if motives are weak—things only noted in reflection, but not felt as compulsions—then they do not restrict us and we are absolutely free (as for Sartre). In the latter case, motives are so weak as to be irrelevant to understanding responsibility for action. The cross-country skier has chosen her own path across the plain.

We can learn nothing by looking at the natural geography because it contributed no momentum and did not restrict or guide her course.

If you have nothing to say about freedom, what is nature?

Nature refers not only to the “slope,” static beneath existence. Nature lies at the heart of subjectivity as well as around it. Nature happens not only “over there” but within. Nature throws into history and all of history is nature thrown forward. “I am thrown into a nature, and that nature appears not only as outside me, in objects devoid of history, but it is also discernable at the centre of subjectivity.”

Nature refers to the entire unfolding drama of the analogy: to the many skiers, to the dynamic play in time of their movement, to their desire to move forward and to whatever movement set them on their way.

The skier perceives all this and does not perceive it all; she perceives Nature not just beneath her, but within her, around her, before her—and yet she can focus only on the features relevant to her speed, her course. We are in time, in natural time. The analogy of the skier amplifies the sense of speed in our dialectic, but the comparison is precise: we cannot reverse our direction in time nor willfully stop, not even for reflection.

So did the skier choose to be here?

The skier cannot go anywhere—the force is too strong. She cannot fly to some other hill in the Alps if she began in the Cascades. But she can redirect her course, adjust her original path. Our trajectory must still fall within a certain range of action.

Not anything is possible.

Not anything is possible?

That is key to thinking. Choice is not equivalent to absolute freedom.

What the difference between choice and absolute freedom are is less clear.

Absolute freedom is cold, cold. Choice is hot. Determinism, hotter, burns away the self, burns away responsibility.

How cold is our skier?

This skier is cold, but she is moving. It is not absolute zero, but the sun is not as close as it is in the summer.

The skier makes a continual effort over time. The effort keeps her warm. Keeps her alive.

The continual effort hides from us, as invisible as her effort to remain upright and oriented to up and down. But without that small effort on the part of her whole being she would lose that sense of a world.

So she is still moving?

Yes. She makes an effort. We make an effort.

She makes an effort in time. As a subject, she makes an effort in time to be a subject. And yet she makes no effort to be a subject. She is.

Time is an effort you cannot cease until you cease.

Either the skier is free and making all choices. Or, the skier is not free and nature has made all the choices.

So, did she choose?

One alterative is motivation. Let’s think of this skier as she is.

She wants to ski, she wants to get to the bottom of the hill. Maybe she just wants to move. She wants to go home and get warm.

The skier’s “motive and decision are two elements of a situation.”

Where in our metaphor is the beautiful life?

You mean, ought we expect the skier to ski beautifully?

Comparing the movement of life to that of art suggests the insertion of criteria of judgment, beauty, and intention into the very practice of action. If we compare action to an artwork, then we might consider extending that analogy to judging the action as we judge an artwork. Just as there are good and bad, successful and unsuccessful poems or paintings, there are successful and less successful actions. From there, we might consider how we understand right action as judged over the whole of a life and personal style. In Greek virtue, ethics as action would be kalon, beautiful when performed well.

We not only choose, but we have the opportunity to make beautiful choices.

In this sense, the analogy to artwork might be troubling on two counts if taken too far. First, the analogy suggests that someone might be able to see the total style of our life and judge it. But the totality always exceeds perception and even reflection.

Well. Where is the self?

A static (or dead) body is not a body for existential philosophy any more than for a medieval Thomist. I unfold in situation.

St. Exupery flew over the fields of Germany and bombed it while Merleau-Ponty watched Paris decay. They took it to heart. “Your act is you,” they said.

Your act is you. Yours. Alone?

And yet it seems that, in the moment of action, we cannot see the canvas.

It is cold here. I don’t ski. Can we go home?

There is nowhere to go. Here on the slope, the “center is everywhere and its circumference nowhere.”

The end of thinking is nowhere.

We are here together.

The momentum of loving drew us through all those choices.

She senses herself caught up in a movement and drawn ahead of herself by a motivation: “Each time I experience a sensation, I feel that it concerns not only my own being, the one for which I am responsible and for which I make decisions, but another self which has already sided with the world.” The sensation of some specific color, for example, “arises from sensibility which has preceded it and which will outlive it, just as my birth and death belong to a natality and mortality which are anonymous.”

There are no names for the voices.

Circa, 2017.

II

Either

is either

One or the other of two:

There are two roads into town, and

You can take either.

or

Each of two:

There are trees on either side.

Either will do. You can go

By either. When you do,

You may sit at either end of the table

For two,

One or the other,

Whatever either

Of you two

Choose to do.

Also, too,

As well, to the same degree, as in:

He is not fond of parties, and I am not either,

Neither him nor me. As in

If you do not go, he won’t come either.

If you do and you don’t

Leave, he won’t either.

If you leave, there are two

Roads from town, and you can go

By either. There are trees

On either side, and either will do.

He doesn’t mind quiet, and neither do you.

If you don’t write after, he won’t either.

Either is good. Eith

er will do.

And what would you say

Of the other two?

Either come or don’t, either stand or sit

Either side of the table, either stay or leave

Either way, left

Or right,

But whatever you do, remember it’s never

One and the other of two.

Circa, 2016.