[extraction]

Jihoon Park

The Tar Divers

The oil well, built on the edge of that enormous tar lake in the heart of the savage steppes, produced forty barrels a day, and yet our benefactor, Duke Arlington, was only interested in the secrets that lay deep beneath. His mechanics were at work designing a great diving bell that could withstand the oppressive pressures of the tar lake and descend to the bottom. One could even say that the entire operation, the drilling, the building of barracks, dining halls, and outhouses, the skirmishes with the natives, was all to fund his eccentric tastes in ancient oriental artifacts.

In the early days of the colony we faced much resistance from the steppe natives, as the drilling area had been a holy burial ground thousands of years ago. We were mostly carpenters and blacksmiths by trade. We built wooden bunkers around the colony to fend off attacks. The oriental men, despite their prowess with bows on horseback, were easily shot down with rifles. They charged us every day until only their young, their old, and their women remained. In the distance we often saw pillars of smoke rising from their village, which we later discovered were from funeral pyres.

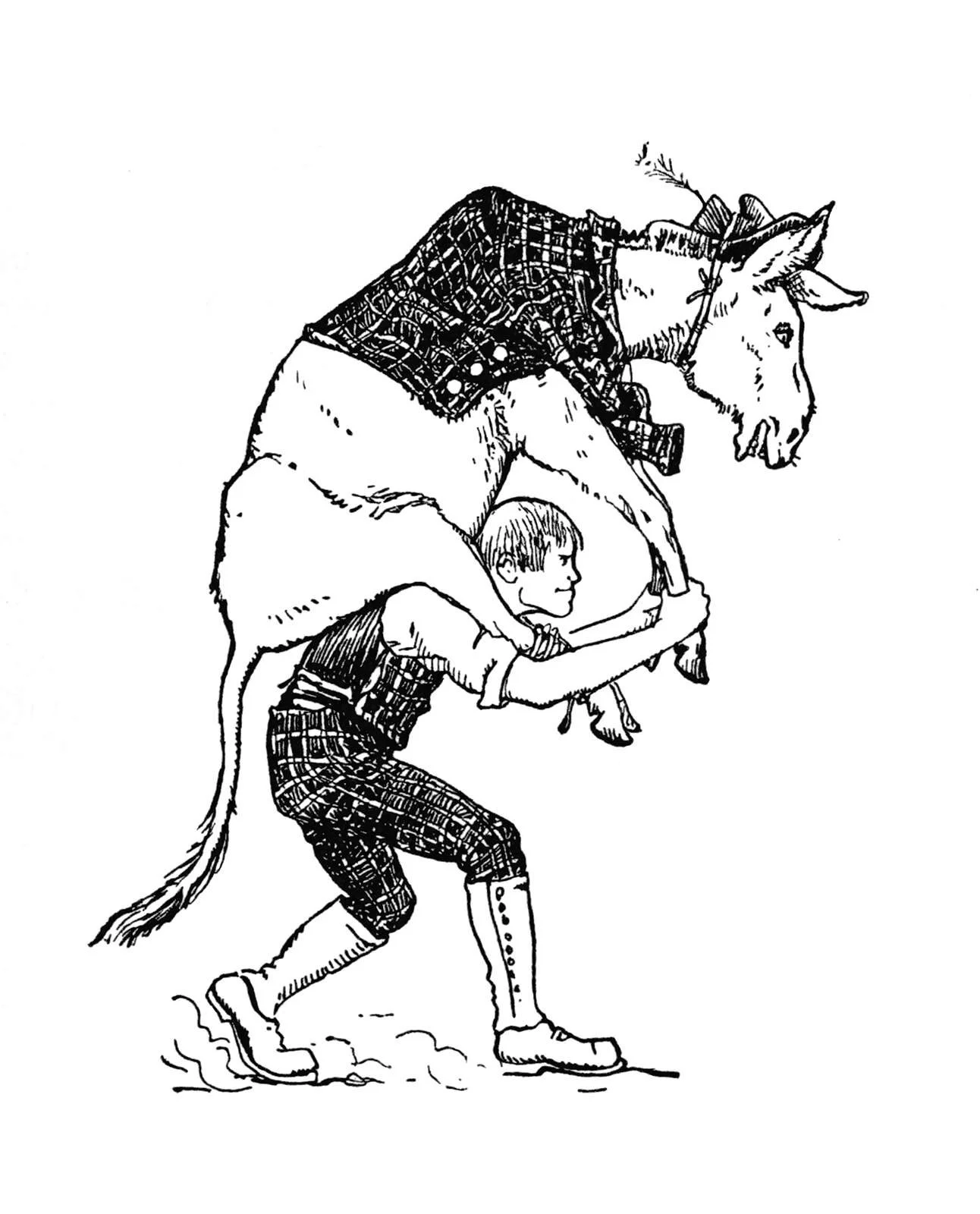

Not all was in vain for the natives. Once the skirmishes stopped we established diplomacy by returning some of the horses we had taken from their fallen men. We traded copper and tin for dried horsemeat, fermented milk, livestock, and raw materials we lacked in the colony. We even traded the oil we drew from their land, which they themselves had no way of extracting and refining. When Greenfield, our dynamite man, was killed in a peat ditch by a falling piston (we had a marmot infestation, they kept chewing our ropes), we decided to hire one of the young oriental men to work for us in exchange for oil. We made a festive occasion of it, putting on a contest to see which of the village youngsters could carry a donkey the longest. We cheered and drank as we watched. By nightfall only three were left. Their shoulders blistered, their knees buckled, and the donkeys grew more ill-tempered every minute. When our whisky ran dry the contest became tiring to watch, so we hired all three remaining youngsters. They were apprentice archers and had tough, calloused hands, hands we soon molded for pickaxes and sledgehammers.

My friend Clements, who first convinced me to leave my family and join the colony, was struck by a swinging counterweight and fell into a reserve pit, breaking both arms and legs. The day before he was scheduled to be sent home along with a shipment of oil, the oriental girl he was sleeping with rubbed some sort of ointment on his injuries. The next day Clements was dead. We suspected she had poisoned the ointment so we shot her. Accidents were common in the colony. The Burns twins, out drunk one night, slipped and fell into the thick tar. Johansson was clearing away rocks in one of our deepest pits when he ruptured a pocket of oil that drowned him. Krasnivich lit up a stick of dynamite thinking it was a cigar. Good men in all.

I had a native girl of my own to keep me company. I nicknamed her Jane. She showed me the dome tents of her village, the foods covered in exotic spices, the tamed birds of prey, and the dazzling ornate rugs. I traded some silverware for two rugs to send back home, as well as some sort of wooden worship idol for little Anne to play with. But like many of her people, Jane had a very particular musty smell which soon became unbearable during the nights she spent with me. During those nights I missed my Elizabeth's clean, perfumed skin.

Duke Arlington’s geologists theorized the tar lake to be one of the deepest ever discovered at forty to fifty meters. The sunlight only penetrated a few meters from the surface, but since the purpose of that first dive was only to confirm the depth, a light source was not needed. Eggy, the quiet sixteen-year-old from Lickford, drew the short straw. He was barely big enough to fit in the diving suit. We rowed to the middle of the lake. Two men and I steadily fed out the rope as Eggy made his dive. Three tugs on the rope meant he had reached the bottom and we could pull him up. Thirty minutes went by with no signal before we realized the tar was too thick to allow any tugging to be felt. We knew something was wrong when we began drawing the rope in and the tension was too light. The rope was torn halfway through. We had forgotten to check it for marmot bites.

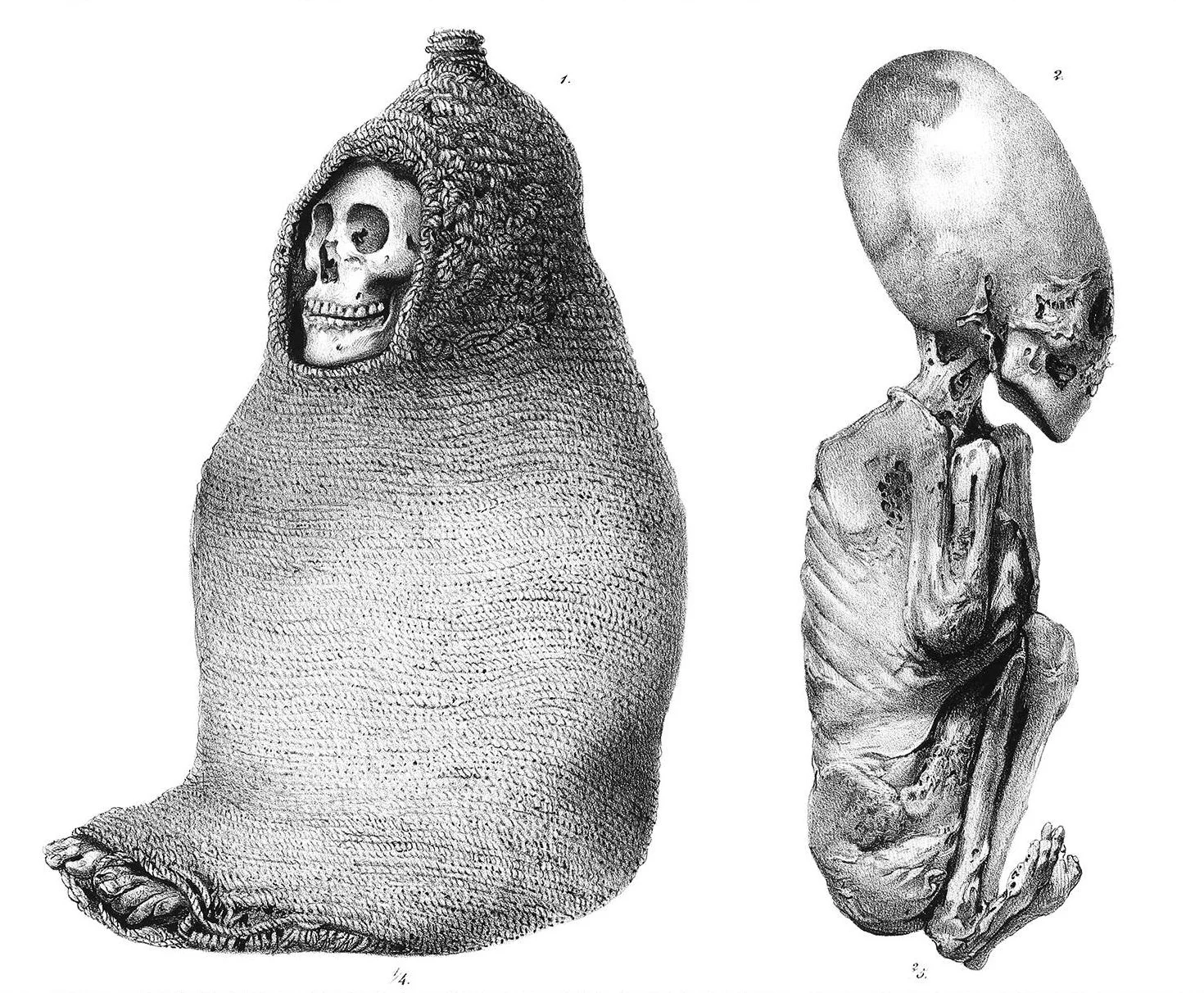

The great diving bell could seat six men and hold enough air for a six hour dive. We were all nervous after the Eggy incident, but Duke Arlington guaranteed our safety and even said he would descend in the bell himself. The bell was hoisted out to the middle of the lake by our two largest boats. As we descended, Griswold, the old guitar luthier, held the lantern with trembling hands, knowing it could easily set the tar beneath our feet aflame. When we felt the ballast weights settle on the bottom, we put on our gear and dove in. With Griswold holding the lantern above us in the bell, we could just about make out the lake bed through the tar. We unearthed a few artifacts of interest, including an ancient headstone and some jewels. We found nothing on our second dive the next day. On the third day we found poor Eggy in his diving suit. The helmet was cracked and filled with tar. The diving bell was at full capacity so we had no choice but to leave the body. Then, on the fourth dive on March 4th, 1877…

We found it! A specimen comparable to the mummies of ancient Egypt, according to Duke Arlington. As we ascended, he took off his coat and cradled the mummy into a little bundle in his arms. When we surfaced, the entire colony was aflame. Burnt bodies pierced by arrows were strewn about. A few survivors were hitching up the remaining horses and wagons. They told us that our three young oriental men, secretly working with warriors from the villages further south, had planned an ambush. Flaming arrows had rained down from all directions. We grabbed what we could salvage and joined their escape.

We were lucky to make it back. Elizabeth adores the oriental rugs (she is the only one among her friends with such rugs) and the wooden worship idol sits next to Anne’s stuffed zebra on her desk. I visited Clements’s family and they wept when I told them what happened. Old Griswold did well for himself, having written a popular tune about the colony, about the natives and the mummy and all the oil we drew. Duke Arlington kept the mummy in his private collection until his death on February 12th, 1882, after which it was moved to the National Museum of Archaeology where it remains as a symbol of our fruitful expedition.

Jihoon Park's fiction is published in Split Lip Magazine, The Columbia Review, and elsewhere. He is a MFA student at George Mason University. He is from San Jose, California.